Love Letter to the Indian River

Tonight I’m sitting down and writing this on a piece of paper before typing it into my computer, because I need to feel the words coming right out of my hands in my particular forms, letters that loop together and spiral across the page like a kind of birdsong growing louder as the sun approaches the eastern horizon, or that ripple across the page like an unexpected breeze on a pond. There’s something about typing on a keyboard right now that feels too urgent. Maybe it’s the tap tap tap of the keys, that have their own music that sometimes sounds like trotting horses or rain falling unevenly on a tin roof. Right now, as the island where I live is giving birth to a new version of itself through a volcanic eruption, I am in need of the sssssss of felt-tip pen on paper, not percussion, gentleness rather than driving on to the next idea as so often happens when I reach a boiling point through the incessant pressure of a deadline and a drum.

These words can be many things, but not all. I shape them with my hands like clay into mugs, fire them in a kiln, offer them to you filled with steeped herbs I gathered myself in remembered meadows, but most of all they are a love letter to the original river that ran through my childhood dreams out back behind my family’s home on Commerce Street.

The river was called The Indian River when I was a kid in Clinton, Connecticut. In the 1970s, nobody, at least not that I knew, thought to question that name. Other rivers nearby were named Hammonasset and Menunketesuck, after actual Indians that had lived in the area before colonization by the white settlers from Europe. Recently, I learned that the neighborhood where my parents now live known as “The Reservation,” bears that name because it was land granted by the white settlers to the remaining natives after their land was claimed by the colonizers. The Indian River probably was named that because that’s where the Indians lived. I’m sure it had another name, but it’s been lost, which makes me sad in so many ways, ranging from a poet’s longing for the specific to despair at the way humanity is still perpetuating the atrocities of war, claiming and conquering, when there is truly enough on this planet for everyone.

But my sadness may not be what the river needs. Maybe the river needs my joy more. Maybe the ghosts who died in despair by the side of the river want to be invited to dance again, even if they will never again be in bodies. Maybe the river needs me to drop judgment and just remember how beautiful it was to walk its edge as a child when I was on the edge of self-consciousness, just becoming aware of what price was required to live in the world-knowing I, and everyone one I knew, and everyone on the whole planet, would someday die.

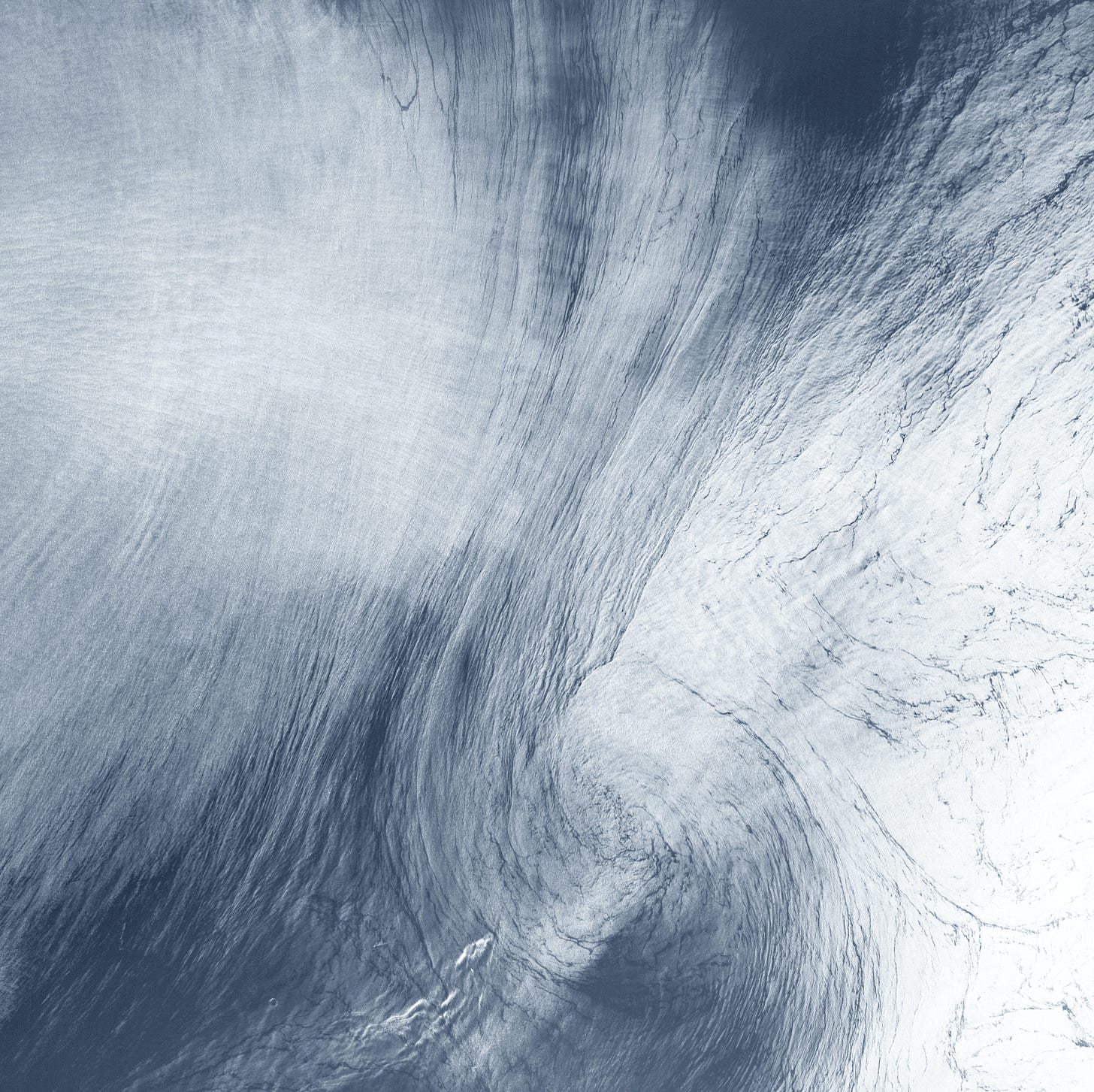

I’m not revealing this to incite woke outrage or say the river’s name should be changed to whatever the indigenous people of Clinton called it, but I am curious. Did the river’s previous name sound like the bend where the water stilled and sometimes circle upon itself in a mysterious eddy before dispersing and moving on toward Clinton Harbor, then Long Island Sound?

I used to be so angry. Now, I find more often I’m just curious. What is the name of the smell of marsh at low tide? Or a slow-moving, not scary at all snake that sometimes freezes over in winter? Or the unnerving hiss of an army of fiddler crabs climbing out of the trenches to move through the marsh grass at low tide toward solid ground? If we are to rename the river, let us listen first. Going back to the old name will be a political statement. We can do better.

So this is my love letter to the Indian River where I first recognized solitude as a calling and a blessing. The river knew I was a poet, long before I did. I wandered alone there in the muck, lay down in the salt meadow. Once I found three abandoned kittens and brought them home. Only then did my parents know I’d been alone so close to the water. Nobody forbid me the river or told me to be careful. I thank my parents for that. I was eight years old and could take care of myself in my little kingdom, the river’s curve where white egrets blazed like initiatory fires and bitterns hid, camouflaged in the grass until something startled them into revealing themselves. Even then I never saw one take to the air, just a harsh croak that sounded like they were choking or being strangled.

At eight I was just beginning to realize I was a self, not just a body enjoying or suffering in the world. Sometime in my eighth year, I split in two in that marsh by the Indian River, watching myself from above step carefully from tussock to tussock, so as not to sink up to my ankles. The split got wider and wider. A lot happened in those years we use to measure the span of a human body circling the sun. I’m sure it did for you, too. But the water circled back for me and I began my return. I came back to that original bend and found myself pierced with holy joy when I saw the white egret. It had nothing to do with me and was the most beautiful thing in the world, an absolute mystery, as were all the people I’d ever known. That mystery was the greatest wonder and still is. The egrets and all the other animals don't seem to need a purpose, or suffer from amnesia. They are content within a containment I can’t imagine. Remembering is not their guide, or prophecy. They are the memory and the prophecy.

The river may have lost one name, but it will have others. This is my love letter to the names we don’t know.

I saw the lava river flowing down the mountain’s flank three nights ago. Mauna Loa, the Long Mountain. This was a burning river, but its motion was the same as the slow, brown snake out back of my childhood home. Even going downhill, it is serpentine, the burning river.

The spiral is all we are and everything else. So often, on the inner and outer journey, we search for the center, but the center can’t be reached because it doesn’t exist. If we reach the center, we no longer exist. We archive the moments we think we reach the center, but those are just stories, useful stories, we can to those who’ll come after, guideposts on the journey in and out.

But the river knows, even though its flowing in one direction, the water its made of is all spiral. There is only the inward draw and the hurling forth.

The river knows, the river knows.

Kō aloha la ea

Concentrate on love by way of the light,

Jen