Dear Readers,

I continue to wonder how folk tales can have a practical application in today’s world. Just writing that sentence feels a bit blasphemous. In general, I don’t favor reductive statements that translate the mysterious into the practical, but I truly want this Substack to be of service, so I’m continually checking in to see what language I should be speaking each week when I write to you. Will it be a poem or a story? Would an essay with a clear thesis be the greatest contribution? I do my best to listen and hopefully get it right more times than not, but lately when I think about writing essays I get a feeling of sick dread. This could be laziness on my part. The amount of thinking that goes into an essay exhausts me. It could also be an inner resistance to change. I, for one, know that sometimes a certain state of agitation must be reached in order for a leap to occur. It could also be a message saying enough. Get out of your head and feel for once.

I do think a couple of general statements about my viewpoint would be useful since a lot of new readers have subscribed lately who may not have read earlier posts. (They are all available in the archives).

One is that when I talk about masculine and feminine, I am referring to inner principles that are not connected to gender. Everyone has an inner masculine and feminine regardless of their gender. If I’m referring to gender I use the words man/woman, male/female, non-binary or trans.

Second, I believe that patriarchy, a culture of control and domination, is the result of a mass distortion of the masculine principle. This means that I, as a gendered female who contains both principles, bear some responsibility for the results of patriarchy.

One of the things I have done to make corrections is get to intimately know my own inner masculine in order to return him to his proper role as a hero. (The role of the inner feminine is to create safety and be the leader. (These ideas are from the Mū doctrines and shared with me by Ke’oni Hanalei.) This mirrors what science knows about how the feminine right brain encompasses the masculine left brain. For a lot more detail read The Master and His Emissary by Iain MacGilchrist.)

As to why the distortion occurred, to put it simply, we are participants in immense, and perhaps impersonal, cycles that our imprisonment in the left brain hemisphere makes difficult, if not impossible to perceive, let alone comprehend. I could write a big long essay about this, but to be honest, I don’t have the energy for it right now and I’m not sure it would do anything but create more agitation, skepticism and divisiveness in the world, so I’m going to turn to a story today and show you what happens when the masculine in the form of a human man feels remorse and makes an act of atonement.

Before I do that, I’ll also state something you may have heard about folk tales, but bears repeating in case you haven’t heard it. One way of listening to stories we’ve gleaned from Jungian depth psychology, is to consider that every character in the story is an aspect of yourself. This practice may not be how the original cultures viewed their stories, but as far as my personal grown goes, and many I know, it’s been enormously fruitful.

I’ve been blessed to sit in the room with some great storytellers, namely Robert Bly, Gioia Timpanelli,

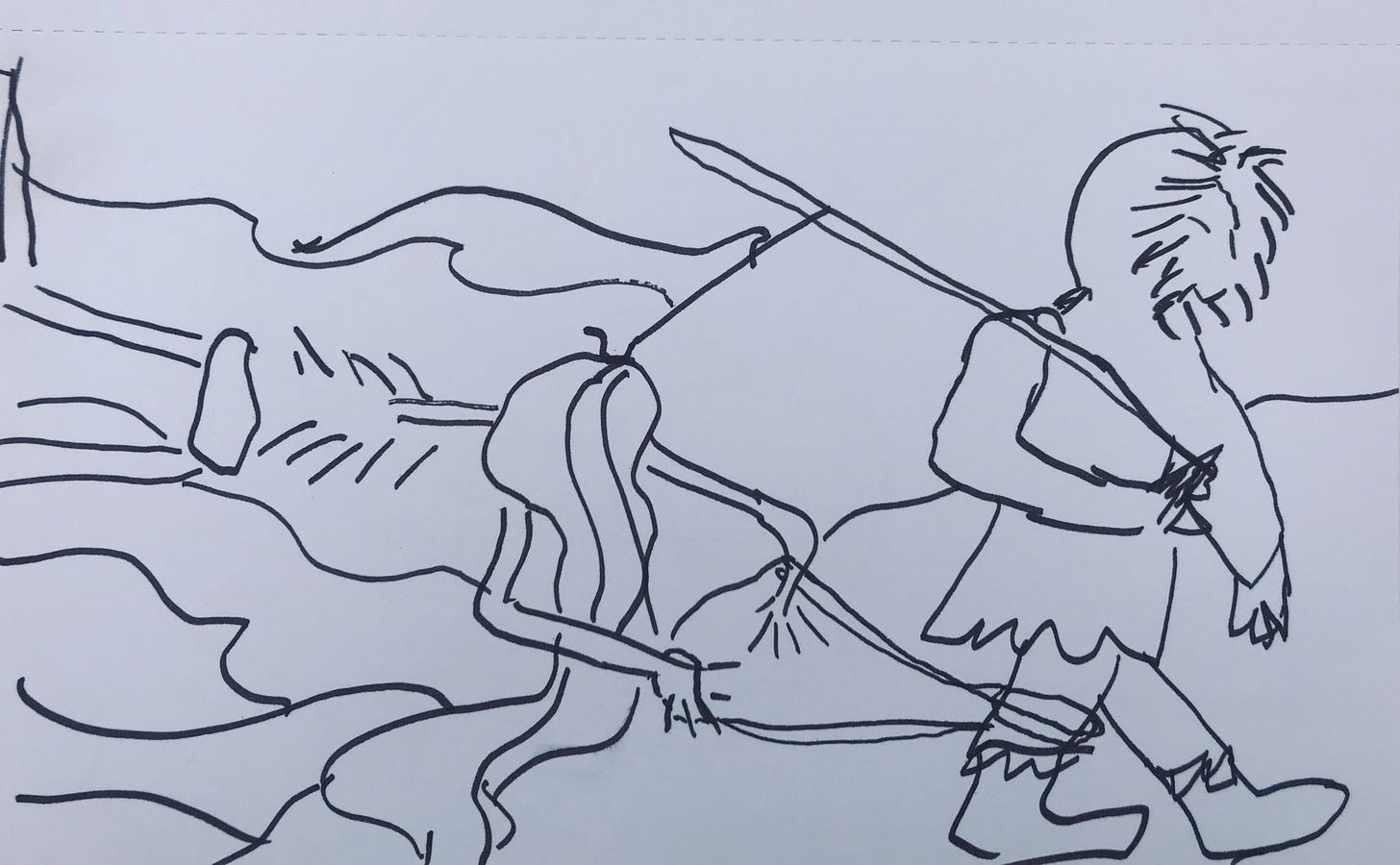

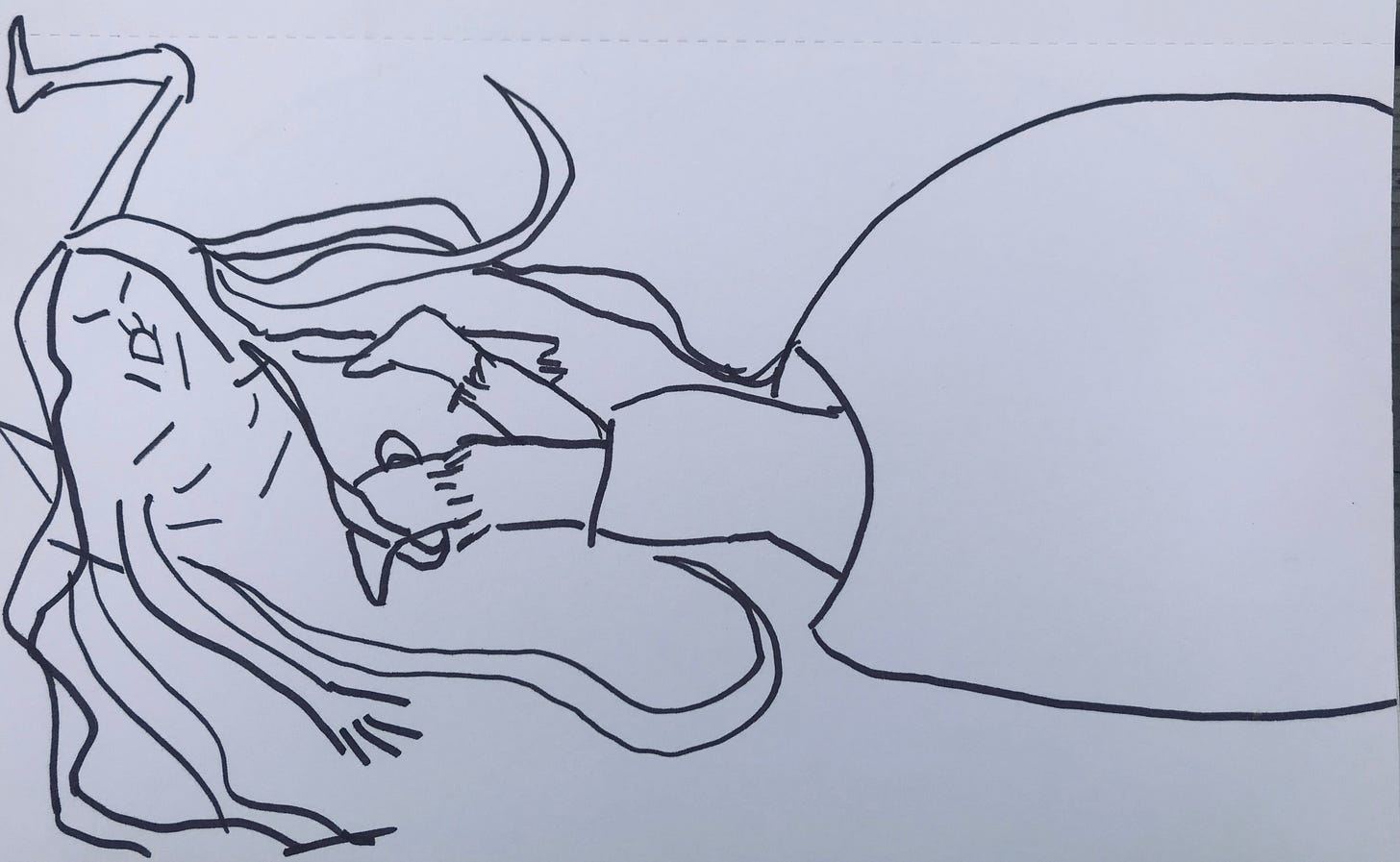

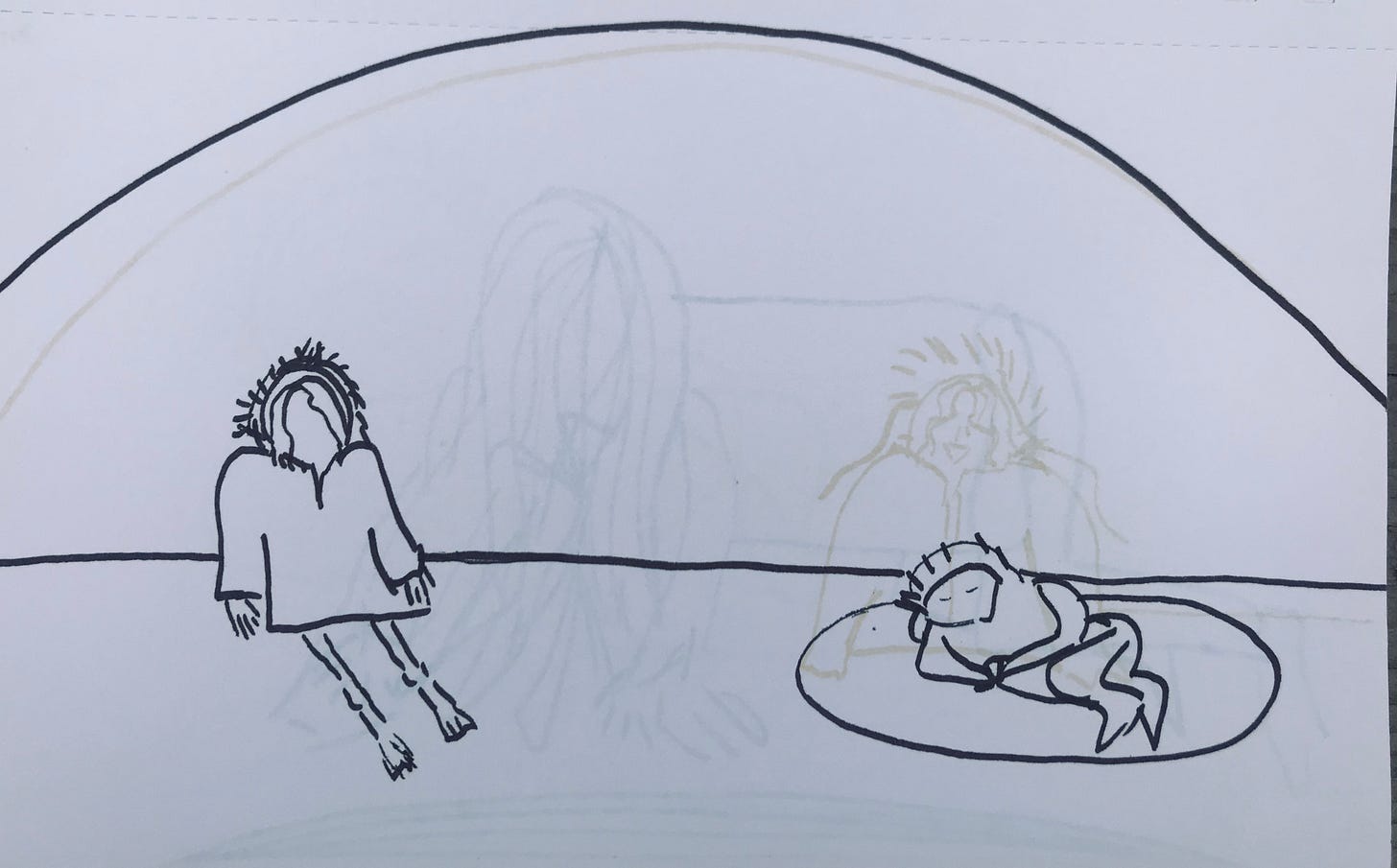

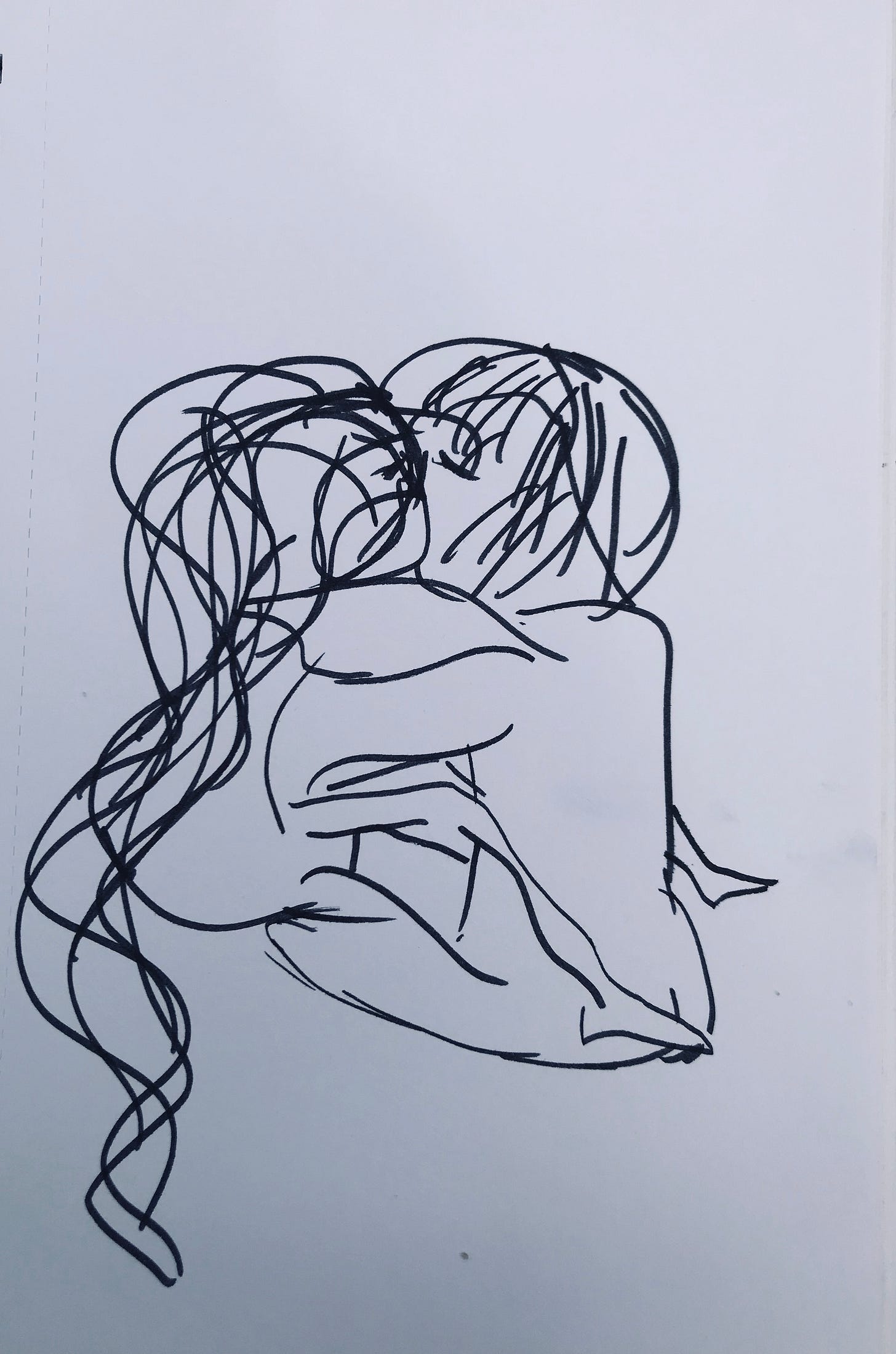

and Jay Leeming. Through Martin I learned the practice of feeding the story. When the story ends, before delving into the analytical, he asks us to feed the living being of the story with whatever image grabs us. Where is that punch in the gut, that gasp, that image that made your heart skip a beat or burst in joy or sorrow?So that’s what I’ll ask of you as you read this week’s story, Skeleton Woman. It’s an Inuit tale I first read in the famed Women Who Run With the Wolves, by Clarissa Pinkola Estes. To me, it’s one of the most beautiful and moving stories I’ve ever encountered. A few years ago I made some sketches to it which I’m including here. Forgive the slight bleed from the backside of my notebook pages.

I’d love to hear from you in the comments what image strikes your heart and soul. Let’s feed this story and let our left brains relax, let go of categorizations and accept that we are enveloped by mystery. Consider we don’t have to figure everything out in order to lead a good life.

Note: There is a link to a wonderful musical rendition of this story inspired by Estes’s book at the bottom of the page. You might want to turn it on before you begin reading.

Skeleton Woman

Nobody remembers why my father threw me over the cliff. No explanation. One minute I was sitting on the long house floor scraping a seal skin, the next I was being dragged by the hair scattering screaming auks whose screams pummeled me on the way down. The ocean cracked like lightning when I broke its surface. My heart fell right out of the hole that was my body. Down, down, down I fell, fish eating my flesh, plucking my eyes out. Blind and nothing but bones, I hit bottom.

One day a fisherman came to the bay where the currents rolled my bones and dropped a line. He was from away and didn’t know the other fisherman never fished here because the place was haunted.

Unaware, he dropped his line and let the current take it. Down, down, down, it dropped. I could feel its shadow but I couldn’t move. The hook found me. Right in the ribs it latched on. I was caught.

When the fisherman felt the heavy tug on his line his heart leaped for joy. He’d caught a big one! He’d be able to feed his village for a long time with this fish. He started to pull the line in, but by now my instincts had kicked in and I started to struggle to disentangle myself. The more I struggled, the more the line tangled until my skeleton was all twisted, bones akimbo. Our struggle caused a tumult in the water and white waves frothed on the surface, rocking the fisherman’s kayak to the point it almost tipped.

The fisherman kept pulling on the line, no idea what he was dragging up. With the hook dug into my ribs, I rose until my skull broke the surface. The fisherman didn’t see me at first because his back was turned, fiddling with the net he was going to use to land his big catch. When he turned and saw me clinging to the bow of his kayak by my teeth he almost leaped out of his skin. Agh! he screamed. Grabbing his paddle he beat me off and began stroking for shore like he was being chased by demons. He was so terrified he didn’t realize I was just tangled in his line. Aggghhh! he kept screaming, jerking me through the waves until the kayak struck shore with a thump.

When he jumped out and started running, fishing stick in hand, I bumped along behind him, bones snagging on rocks, until we reached his igloo. Gasping for breath, he ducked and slid into the dark dome where he collapsed in a heap in a pile of furs. I could hear him sobbing-in relief. The living drum of his heart pounded in his chest.

What he didn’t know, is that he’d dragged me into the igloo, too. I lay in a crumpled heap near the door. When his breath had slowed, he lit an oil lamp and saw me. Agghhhhh! He cried again. The whole tundra shuddered.

One heel was over my shoulder, one knee inside my ribcage, one foot over my elbow. I wasn’t going anywhere. I was a fright for sure.

After a time, after I hadn’t risen up and strangled him or cut his throat, I could feel the hunter’s gaze had changed. His breathing had slowed. He came closer. I was blind, but I swear I saw a look of his kindness on his face. The light from the whale oil lamp flickered and grew stronger.

He began to sing, a lullaby, like I was a sleeping child. His hands followed with the same tenderness, untangling the line that had so twisted me up. “Oh, na na na,” he sang. “Oh, na na na.” First he untangled my toes, then my ankles. He untangled my knees and my long thighbones, unwound the line from the bowl of my pelvis, freed my ribs, my arms and clavicles. When the line was loose and my skeleton was back in order, he wrapped my bones in furs to warm me.

I kept silent. I didn’t dare speak. I couldn’t remember the last time I was warm. I’d forgotten tenderness even existed. As I watched him carefully oil his fishing stick and rewind the line that had snared me, I waited for him to come to his senses and strip the fur off my bones, drag me out of the igloo and toss me over the cliff where my bones would shatter into pieces that could never be recovered.

Finally, he finished his tasks. He was tired. He had paddled far today through the white water, fought a battle with a tangled up skeleton fueled only be terror. I watched his eyes droop. He yawned. Still, he didn’t slide under his sleeping skins until he’d built the fire up so I wouldn’t get cold in the night. When that was done, he slipped under his skins and was asleep as soon as his eyes closed.

Soon he was dreaming. I don’t know what he dreamed of, but whatever it was brought me closer. He looked so innocent sleeping there under his furs in the presence of something that had terrified him so much. That something was me. The man trusted me enough to fall asleep, enough to dream.

I don’t know what he saw in his sleep, but I felt his longing. Or his sadness. Sometimes they’re the same thing. And then I saw it. Closer, I came, drawn by his dream.

In the fire’s flicker, something sparkled in the corner of the man’s eye. A glistening tear had slipped out from under his closed eyelid. As I watched it swell, I was struck by a great thirst. I had never been so thirsty. It had been years since I’d drank.

With painstaking care not to wake him, I clattered across the floor until my face was so close to his I could feel his breath and without thought I put my mouth to the tear and drank. And the tear became a river, and the river became a waterfall. I drank and drank and drank. The water was unending.

The man dreamed on. Laying beside him, I reached under his sleeping skins and into the sleeping man himself. I took his heart out. The very drum inside him. Ba boom, ba boom, ba boom, I beat on his heart. I was the drummer now. I began to sing:

Flesh! Flesh! Flesh!

I sang the flesh back onto my bones. I sang for long hair and far-seeing eyes and nimble hands. I sang for breasts long enough to wrap around myself for warmth and a cleft between my legs. I sang for all the things a woman needs, a flesh and blood woman, and I didn’t stop until I had them.

Only then did I sing his clothes off and slip under the furs and lie with him skin to skin. I returned the great drum of his heart to his body.

We awoke in the morning entangled, this time in a good way, a lasting way, and those who forgot why my father threw me over the cliff say we are still wrapped around each other, and we are never hungry, for the creatures under the sea who looked after me all the time I was a skeleton feed us. Warm and well-fleshed we are. And the sea sings.

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="

Kō aloha lā ea

Concentrate on love by way of the light

It seems to me the odds have often been impossible, and yet our ancestors managed to get us here. All praise to all of them, human and otherwise.

I really like the comment that our inner masculine has work to do to restore the inner masculine's culturally repressed characteristics, and I'm thankful to know many young/old folk who are doing this work. There were many moments for me in your retelling of Skeleton Women from this foundation: from when he leaves to fish, his terror, his unwrapping his fishing line/reassembly of her, his exhaustion, her drinking the tear and especially her singing herself into a fleshly being capable of being "entangled" in a shared relationship of joy.